It’s hard to resist adding my $0.02 in a debate about blogging like the one Nick Carr started this week with his post on The Great Unread, the story of the royal hierarchy in the blogosphere:

“As the blogophere has become more rigidly hierarchical, not by design but as a natural consequence of hyperlinking patterns, filtering algorithms, aggregation engines, and subscription and syndication technologies, not to mention human nature, it has turned into a grand system of patronage operated – with the best of intentions, mind you – by a tiny, self-perpetuating elite.”

It’s definitely worth a read if you blog. If you don’t, it’s more echo chamber music, as is this post.

I suspect that the idea of the blogosphere and the blog elite is a temporary one. The blogger hierarchy does not make the substance of a post any more or less valuable. Ultimately, that value is completely up to me, not some shallow power structure.

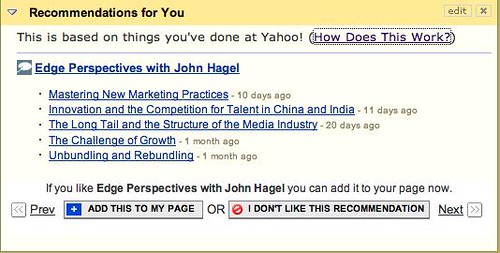

I’m hoping that instead of reinforcing global hiearchical power structures that things like recommendation engines, personalization services, syndication and filtering algorithms will weed out the crap and bubble up what matters to me, empowering me to own my media experience.

Popular blogs, podcasts and videos will become just a sidebar to my daily intake when their relevance to my world is only tangential.

I respect what Jay Rosen says (and Nick, for that matter), but his posts are too long for me. I need the blogs I read regularly to filter out which of Jay’s posts are worth spending the time to read. I’m impressed not just by the quality of the posts Jeff Jarvis generates but also the volume. Again, I need an interestingness filter on Jeff’s posts to surface the ones that matter to me.

Yet all of Jay’s and Jeff’s influence on my thinking about journalism and media has no bearing whatsoever on the music I listen to, the basketball teams I follow or the technologies I find interesting.

What Nick rightly points out is that there will be an increasing tendency for people to publish for the sake of fame and fortune which will dilute the pool of interesting things out there. This is the popularity problem.

Perhaps I’m just optimistic. But it seems reasonable to expect that we’ll find technology answers to this issue, automatic ways to subvert wasteful power structures that may be forming in the world of personal media.