In January 2007 a well known computer scientist named Jim Gray was lost at sea off the California coast on his way to the Farallon islands.

It was a moment that many will remember either because Jim Gray was a big influence personally or professionally or because the method of the search for him was a real eye opener about the power of the Internet. Â It was a group task-based investigation of epic proportions using the latest and greatest technology of the day.

I didn’t know him, but I will never forget what happened.  Not only did the Coast Guard’s air and surface search cover 40,000 square miles, but a distributed army of 12,000 people scanned NASA satellite imagery covering 30,000 square miles.  We all used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to flip through tiles looking for a boat that would’ve been about 6 pixels in size.

I didn’t know him, but I will never forget what happened.  Not only did the Coast Guard’s air and surface search cover 40,000 square miles, but a distributed army of 12,000 people scanned NASA satellite imagery covering 30,000 square miles.  We all used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to flip through tiles looking for a boat that would’ve been about 6 pixels in size.

They attacked the search in some phenomenal ways.  Here is Werner Vogel’s public call for help. You can also go back and read the daily search logs posted by his friends on the blog here.  Both Wired and the New York Times covered this incredible drama in detail.

Since then we’ve seen the Internet come to the rescue or at least try to make a difference using similar crowdmapping techniques.  Perhaps the most powerful example is the role crisis mappers and the Ushahidi platform played in the major Haiti earthquake in 2010.

But it’s not just crisis where these technologies are serving a public good. Â We’ve seen these swarming techniques applied in a range of ways for journalism and many other activities on the Internet.

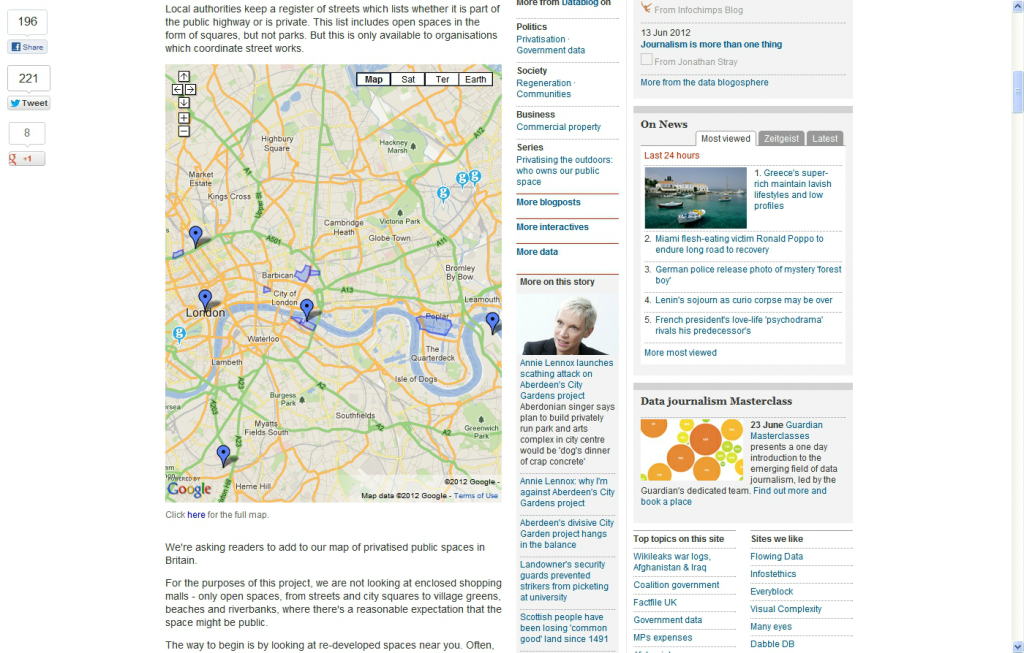

Perhaps the gold standard for collective investigative reporting is the MPs Expenses experiment by Simon Willison at the Guardian where 170,000 documents were reviewed by 15,000 people in the first 80 hours after it went live.  The Guardian has deployed its readers to uncover truth in a range of different stories, most recently with the Privatised Public Spaces story.  We’ve also looked at crowdmapping broadband speeds across the UK, and Joanna Geary’s ‘Tracking the Trackers‘ project uncovered some fascinating data about the worst web browser cookie abusers.

Last year Germany’s defense minister Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, a man once considered destined for an even larger role in the government, was forced to resign from his post as a result of allegations that he plagiarized his doctoral thesis. Â It was proved to be true by a group of people working collectively on the investigation using a site called GuttenPlag Wiki.

ProPublica is a real pioneer in collective reporting and data journalism.  For example, their 2010 investigation into which politicians were given Super Bowl tickets provided a wonderful window into the investigative process.  And the Stimulus Spotcheck project invited people to assess whether or not the 2009 stimulus package in the US was in fact having an impact.

Also, Kevin Anderson reminded me of http://www.ipaidabribe.com tracking local corruption and http://oilreporter.org/ which came out of the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill in 2010 and helps people report wildlife damage, share photos, etc.

Of course, swarming projects can have a range of different intentions, and if one were to try and count them I would bet only a small percentage are high impact journalistic endeavors.

Andy Baio is a pioneer in this kind of concept and has either been the curator of data already in existence or the inspiration for a crowdsourced investigation.  For example, his “Girl Turk” collective research uncovered an exhaustive list of artist and track names sampled for Girl Talk’s Feed the Animals album.

The big advertising brands intuitively understand the power of swarming intelligence, too, as they see it as a way to use their loyal customers to help them acquire new customers or to at least build a stronger direct relationship with a large group of people. Â This is essentially the pitch once used by MySpace and adopted by Facebook, Twitter and Google +…Step 1: create a brand page where people can congregate, Step 2: inspire people to do something collectively that spreads virally.

The technologies that make these group tasks possible are getting easier and more accessible all the time. The wiki format works great for some projects. Â DocumentCloud is a tremendous platform. Â Google Docs are providing a lot of power for collective investigations, as we’ve discovered several times on the Guardian’s Datablog. And, of course, crowdmapping can be done with little technical intervention using Ushahidi and n0tice.

Of course, you can’t discount the power of the social networks as distribution platforms and amplifiers for group-based investigations. Â Creating the space for swarming activity is one thing, but getting the word out is a role that Facebook and Twitter are very good at playing. Â It’s a perfect marriage, in many ways.

An army of helpers may be accessible in other ways, too.

Amanda Michel who famously drove the Off The Bus campaign at HuffPo (more on that below) produced a guide to “Using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk for Data Projects” while at ProPublica where she describes how they hired workers to complete short, simple tasks.

But I imagine that the next wave of activity will arise as some of the human patterns of group tasks inspire more sustainable technology platforms. Â As Martin Kotynek and ‘PlagDoc’Â acknowledge in their wonderful report “Swarm of thoughts” there’s a need for some sort of centralized research platform so this kind of activity is easier to trigger and run with.

Perhaps it’s a matter of identifying a few very specific collective research concepts that work and fueling ongoing community activity around those ideas. Â Citizen journalism, for example, is an obvious activity where communities are forming.

CNN’s iReport has a ready-built citizen journalist network incentivized by exposure on cnn.com, and the n0tice platform can enable citizen-powered crowdmapping activity for a range of different projects and get exposure and distribution across different platforms.  Both are capable of serving an ongoing role as useful every-day citizen journalism services that can crank up the volume on a particular issue when the appropriate moment arises.

Platforms can create some ongoing momentum, but so can issues.

Off The Bus was an 18-month HuffPo initiative where readers and staff covered the US elections collaboratively from their own communities. The project had the additional benefit of generating insights that turned into larger editorial investigations such as the Superdelegate Investigation, a report on the Evangelical Vote and the Political Campaign HQ crowdmapping project.  Ryan Tate’s book The 20% Doctrine goes into some detail about Off The Bus, how it developed, and how Amanda managed it all.

Off The Bus was an 18-month HuffPo initiative where readers and staff covered the US elections collaboratively from their own communities. The project had the additional benefit of generating insights that turned into larger editorial investigations such as the Superdelegate Investigation, a report on the Evangelical Vote and the Political Campaign HQ crowdmapping project.  Ryan Tate’s book The 20% Doctrine goes into some detail about Off The Bus, how it developed, and how Amanda managed it all.

I suspect that a whole class of swarming intelligence projects is starting to bubble up that may only appear when the human story, the technology, and the amplifier join up and create a perfect storm.

In the end, it comes down to projects that resonate with people on a personal level.

Though Jim Gray was never found, the thinking about how to conduct the search amongst the leaders of the crowd at the time could not have been more cogent. Â The instructions for participants were inspiring, detailing a simple task and the result of completing it:

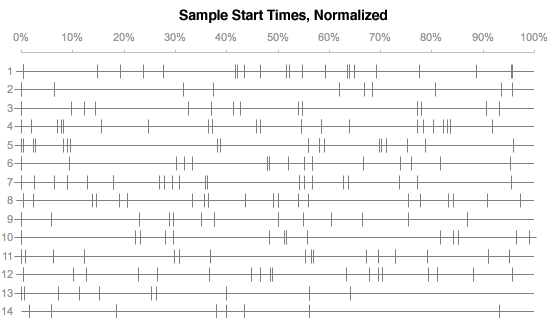

You will be presented with 5 images. The task is to indicate any satellite images which contain any foreign objects in the water that may resemble Jim’s sailboat or parts of a boat. Jim’s sailboat will show up as a regular object with sharp edges, white or nearly white, about 10 pixels long and 4 pixels wide in the image. If in doubt, be conservative and mark the image. Marked images will be sent to a team of specialists who will determine if they contain information on the whereabouts of Jim Gray. Friends and family of Jim Gray would like to thank you for helping them with this cause.

It’s conceivable that the most important thing social media has accomplished over the last 3-5 years is that it has unlocked the natural desire people have to impact what’s happening in the world in a way they may not have felt empowered to do for decades.

Now it’s simply a matter of joining up the technologies in ways that enable those ideas to come to life.

A List of Collective Investigations

Below are some of the projects mentioned above and several others that have been sent to me. Â I’ve included a few things that aren’t journalism investigations that are worth a closer look simply because they can be instructive.

![medium_jimgrayamazon[1]](http://www.mattmcalister.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/medium_jimgrayamazon1.jpg)

A notable omission here is the Public Insight Network, a crowd-sourcing platform used by 70 newsrooms in the U.S and one in South Africa. We’re nearly ten years old, but still get left off of lists like this — I think largely because we’re not an “open” project that anyone can check out & play with, which is actually in some ways why it works so well: It’s a private backchannel for journalists to tap into a very large source network (165,000 sources and growing fast). More here : http://www.publicinsightnetwork.org, or ping me at ahaeg [at] americanpublicmedia.org.

Thanks, Andrew. Fascinating. There are lots of interesting tools and networks that can help people accomplish a distributed group-based investigation, but for this post I’m particularly looking for the interesting investigations themselves rather than the spaces where they happen. Can you point me to any specific task-based investigations performed by the Public Insight Network?