The content previously published here has been withdrawn. We apologise for any inconvenience.

Author: Matt McAlister

The real cost of free

Cory is spot on, as usual.

Last week, my fellow Guardian columnist Helienne Lindvall published a piece headlined The cost of free, in which she called it "ironic" that "advocates of free online content" (including me) "charge hefty fees to speak at events".

Lindvall says she spoke to someone who approached an agency I once worked with to hire me for a lecture and was quoted ,000-,000 (£6,300-£12,700) to speak at a college and ,000 to speak at a conference. Lindvall goes on to talk about the fees commanded by other speakers, including Wired editor Chris Anderson, author of a book called "Free" (which I reviewed here in July 2009), Pirate Bay co-founder Peter Sunde and marketing expert Seth Godin. In Lindvall’s view, all of us are part of a united ideology that exhorts artists to give their work away for free, but we don’t practice what we preach because we charge so much for our time.

It’s unfortunate that Lindvall didn’t bother to check her facts. I haven’t been represented by the agency she referenced for several years, and in any event, no one has ever paid me ,000 to appear at any event. Indeed, the vast majority of lectures I give are free (see here for the past six months’ talks and their associated fees – out of approximately 95 talks I’ve given in the past six months, only 11 were paid, and the highest paid of those was £300). Furthermore, I don’t use an agency for the majority of my bookings (mostly I book myself – I’ve only had one agency booking in the past two years). I’m not sure who the unfortunate conference organiser Lindvall spoke to was – Lindvall has not identified her source – but I’m astonished that this person managed to dig up the old agency, since it’s not in the first 400 Google results for "Cory Doctorow".

It’s true that my stock response to for-profit conferences and corporate events is to ask for ,000 on the grounds that almost no one will pay that much so I get to stay home with my family and my work; but if anyone will, I’d be crazy to turn it down. Even so, I find myself travelling more than I’d like to, and usually I’m doing so at a loss.

Why do I do this? Well, that’s the bit that Lindvall really got wrong.

You see, the real mistake Lindvall made was in saying that I tell artists to give their work away for free. I do no such thing.

The topic I leave my family and my desk to talk to people all over the world about is the risks to freedom arising from the failure of copyright giants to adapt to a world where it’s impossible to prevent copying. Because it is impossible. Despite 15 long years of the copyright wars, despite draconian laws and savage penalties, despite secret treaties and widespread censorship, despite millions spent on ill-advised copy-prevention tools, more copying takes place today than ever before.

As I’ve written here before, copying isn’t going to get harder, ever. Hard drives won’t magically get bulkier but hold fewer bits and cost more.

Networks won’t be harder to use. PCs won’t be slower. People won’t stop learning to type "Toy Story 3 bittorrent" into Google. Anyone who claims otherwise is selling something – generally some kind of unworkable magic anti-copying beans that they swear, this time, will really work.

So, assuming that copyright holders will never be able to stop or even slow down copying, what is to be done?

For me, the answer is simple: if I give away my ebooks under a Creative Commons licence that allows non-commercial sharing, I’ll attract readers who buy hard copies. It’s worked for me – I’ve had books on the New York Times bestseller list for the past two years.

What should other artists do? Well, I’m not really bothered. The sad truth is that almost everything almost every artist tries to earn money will fail. This has nothing to do with the internet, of course. Consider the remarkable statement from Alanis Morissette’s attorney at the Future of Music Conference: 97% of the artists signed to a major label before Napster earned 0 or less a year from it. And these were the lucky lotto winners, the tiny fraction of 1% who made it to a record deal. Almost every artist who sets out to earn a living from art won’t get there (for me, it took 19 years before I could afford to quit my day job), whether or not they give away their work, sign to a label, or stick it through every letterbox in Zone 1.

If you’re an artist and you’re interested in trying to give stuff away to sell more, I’ve got some advice for you, as I wrote here – I think it won’t hurt and it could help, especially if you’ve got some other way, like a label or a publisher, to get people to care about your stuff in the first place.

But I don’t care if you want to attempt to stop people from copying your work over the internet, or if you plan on building a business around this idea. I mean, it sounds daft to me, but I’ve been surprised before.

But here’s what I do care about. I care if your plan involves using "digital rights management" technologies that prohibit people from opening up and improving their own property; if your plan requires that online services censor their user submissions; if your plan involves disconnecting whole families from the internet because they are accused of infringement; if your plan involves bulk surveillance of the internet to catch infringers, if your plan requires extraordinarily complex legislation to be shoved through parliament without democratic debate; if your plan prohibits me from keeping online videos of my personal life private because you won’t be able to catch infringers if you can’t spy on every video.

And this is the plan that the entertainment industries have pursued in their doomed attempt to prevent copying. The US record industry has sued 40,000 people. The BBC has received Ofcom’s approval to use our mandatory licence fees to lock up its broadcasts with DRM so that we can’t tinker with or improve on our own TVs and recorders (and lest you think that this is no big deal, keep in mind that the entire web was created by amateurs tinkering with systems around them). What’s more Apple, Audible, Sony and others have stitched up several digital distribution channels with mandatory DRM requirements, so copyright holders don’t get to choose to make their works available on equitable terms.

In France, the HADOPI "three strikes" rule just went into effect; they’re sending out 10,000 legal threats a week now, and have promised 150,000 a week in short order. After three unsubstantiated accusations of infringement, your whole family is disconnected from the internet – from work, education, civic engagement, distant relatives, health information, community. And of course, we’ll have the same regime here shortly, thanks to the Digital Economy Act, passed in a three-whip wash-up in the last days of parliament without any substantive debate, despite the thousands and thousands of Britons who asked their legislators to at least discuss this extraordinarily technical legislation before passing it into law.

Viacom is just one of the many entertainment giants suing companies like Google for allowing everyday people to upload content to the internet without reviewing its copyright status in advance. Never mind that there’s 29 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute, that there aren’t enough lawyers in all the world to undertake such a review, and that throttling the videos (by charging uploaders for legal review, for example) would put practically every person who finds in YouTube the opportunity for personal and creative expression out of business.

Never mind that if this principle were passed into law, it would shutter every message board, Twitter, social networking service, blog, and mailing list in a second. That’s bad enough, but in addition to these claims, Viacom has asked the court to order Google to make all user-uploaded content public so that Viacom can check it doesn’t infringe copyright – it thinks that its need to look at my videos is greater than my need to, say, flag a video of my two-year-old in the bath as private and visible only to me and her grandparents.

Meanwhile, the entertainment industries continues their push around the world for a series of China-style national firewalls (in the UK, former BPI executive Richard Mollet boasted of getting this legislation inserted into the Digital Economy Act).

This is an approach that millionaire pop stars like U2’s Bono wholeheartedly endorse – last Christmas, he penned a New York Times op-ed calling for Chinese-style censorship everywhere. And just this month, MPAA representatives told the world’s governments that adopting national internet censorship regimes for copyright would also allow them to block information embarrassing to their regimes, such as WikiLeaks.

The MPAA was addressing a meeting for the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, a secret treaty that is being negotiated away from the UN, behind closed doors, and which includes proposals to search iPods, phones and laptop hard-drives at the world’s borders to look for infringement.

So yeah, if you want to try to control individual copies of your work on the internet, go ahead and try. I think it’s a fool’s errand, and so does almost every technical expert in the world, but what do we know?

But for so long as this plan involves embedding control, surveillance and censorship into the very fabric of the information society’s infrastructure, I’ll continue to tour the world, for free, spending every penny I have and every ounce of energy in my body to fight you.

Helienne, I can’t fault you for not reading my Guardian columns; after all, I’ve never read yours. And while I do fault you for not correcting the record, I won’t ask the Guardian’s reader’s editor to intervene or make silly, chiropractor-esque noises about libel. I’m a civil libertarian, and I have integrity, and I believe that the answer to bad speech is more speech, hence this column.

But you really ought to familiarise yourself with the ideologies of the people you’re condemning before you tear into them. I don’t agree with everything Chris Anderson says, but he hardly tells people to give their stuff away: mostly, Chris talks about how different pricing structures, loss-leaders, and sales techniques can be used to increase the bottom lines of creators, manufacturers, publishers and inventors, and he cites case studies of people who’ve made this work for them.

I have no idea what Seth Godin is doing on your hitlist: Seth’s a marketing consultant. The last three times I’ve heard him speak, he’s been talking about how to improve corporate communications and brand identity – that sort of thing. Sure, he apparently charges a very large sum of money for this advice, but that’s the topsy-turvy world of marketing for you. If your point is that creative people deserve to get paid, then presumably you’re all for Seth charging whatever the market will bear.

Now, Peter Sunde is an interesting case. He really does advocate something like totally unrestricted copying. But as you note yourself, this is a belief that he’s prepared to go to jail for, which is generally considered the gold standard for sincerity (the only higher standard I know of is being prepared to die for your beliefs – you should ask Peter where he stands on this). If your point is that Peter is only shamming about his politics, how do you explain this willingness to be imprisoned for them? Also: given Peter’s latest startup, Flattr, exists for the sole purpose of making it simple for audiences to pay artists, I think you might reconsider his place in your parade of villainy.

I understand perfectly well what you’re saying in your column: people who give away some of their creative output for free in order to earn a living are the exception. Most artists will fail at this. What’s more, their dirty secret is their sky-high appearance fees – they don’t really earn a creative living at all. But authors have been on the lecture circuit forever – Dickens used to pull down 0,000 for US lecture tours, a staggering sum at the time. This isn’t new – authors have lots to say, and many of us are secret extroverts, and quite enjoy the chance to step away from our desks to talk about the things we’re passionate about.

But you think that anyone who talks up their success at giving away some work to sell other work is peddling fake hope. There may be someone out there who does this, but it sure isn’t me. As I’ve told all of my writing students, counting on earning a living from your work, no matter how you promote it or release it, is a bad idea. All artists should have a fallback plan for feeding themselves and their families. This has nothing to do with the internet – it’s been true since the days of cave paintings.

You know who peddles false hope to naive would-be artists? People who go around implying that but for all those internet pirates, there’d be full creative employment for all of us. That the reason artists earn so little is because our audiences can’t be trusted, that once we get this pesky internet thing solved, there’ll be jam tomorrow for everyone. If you want to damn someone for selling a bill of goods to creative people, go after the DRM vendors with their ridiculous claims about copy-proof files; go after the labels who say that wholesale lawsuits against fans on behalf of artists (where labels get to pocket the winnings) are good business; go after the studios who are suing to make it impossible for anyone to put independent video on the internet without a giant corporate legal budget.

And if you want to find someone who supports artists, look at organisations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who have advanced the cause of blanket licences for music, video and other creative works on the internet. As a songwriter, you’ll be familiar with these licences: as you say, you get 3% every time someone performs your songs on stage. What EFF has asked for is the same deal for the net: let ISPs buy blanket licences on behalf of their customers, licences that allow them to share all the music they’re going to share anyway – but this way, artists get paid. Incidentally, this is also an approach favored by Larry Lessig, whom you also single out as "ironic" in your piece.

It’s been 15 years since the US National Information Infrastructure hearings kicked off the digital copyright wars. And for all the extraordinary power grabbed by the entertainment giants since then, the letters of marque and the power to disconnect and the power to censor and the power to eavesdrop, none of it is paying artists. Those who say that they can control copies are wrong, and they will not profit by their strategy. They should be entitled to ruin their own lives, businesses and careers, but not if they’re going to take down the rest of society in the process.

And that, Helienne, is what I tell people when I give my lectures, whether paid or free.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

The need for better research

I find Susan Greenfield’s perspective on the future of the human brain a bit alarmist (see below), but it’s clear that we have a lack of knowledge on the impact of the increasingly intertwined connections forming as a result of networks.

I suspect the physical brain damage and enhancements we may be experiencing are less harmful and beneficial than the things people will do to each other because of networked behaviors.

Lady Greenfield reignited the debate over modern technology and its impact on the brain today by claiming the issue could pose the greatest threat to humanity after climate change.

The Oxford University researcher called on the government and private companies to join forces and thoroughly investigate the effects that computer games, the internet and social networking sites such as Twitter may have on the brain.

Lady Greenfield has coined the term "mind change" to describe differences that arise in the brain as a result of spending long periods of time on a computer. Many scientists believe it is too early to know whether these changes are a cause for concern.

"We need to recognise this is an issue rather than sweeping it under the carpet," Greenfield said. "We should acknowledge that it is bringing an unprecedented change in our lives and we have to work out whether it is for good or bad."

Everything we do causes changes in the brain and the things we do a lot are most likely to cause long term changes. What is unclear is how modern technology influences the brain and the consequences this has.

"For me, this is almost as important as climate change," said Greenfield. "Whilst of course it doesn’t threaten the existence of the planet like climate change, I think the quality of our existence is threatened and the kind of people we might be in the future."

Lady Greenfield was talking at the British Science Festival in Birmingham before a speech at the Tory party conference next month. She said possible benefits of modern technology included higher IQ and faster processing of information, but using internet search engines to find facts may affect people’s ability to learn. Computer games in which characters get multiple lives might even foster recklessness, she said.

"We have got to be very careful about what price we are paying, that the things that are being lost don’t outweigh the things gained," Greenfield said. "Every single parent I have spoken to so far is concerned. I have yet to find a parent who says ‘I am really pleased that my kid is spending so much time in front of the computer’."

Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London and co-author of the book The Learning Brain, agreed that more research was needed to know whether technology was causing significant changes in the brain. "We know nothing at all about how the developing brain is being influenced by video games or social networking and so on.

"We can only really know how seriously to take this issue once the research starts to produce data. So far, most of the research on how video games affect the brain has been done with adult participants and, perhaps surprisingly, has mostly shown positive effects of gaming on many cognitive abilities," she said.

Maryanne Wolf, a cognitive neuroscientist at Tufts University in Massachusetts and author of Proust and the Squid, said that brain circuits honed by reading books and thinking about their content could be lost as people spend more time on computers.

"It takes time to think deeply about information and we are becoming accustomed to moving on to the next distraction. I worry that the circuits that give us deep reading abilities will atrophy in adults and not be properly formed in the young," she said.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Mind change – a moral choice? (openparachute.wordpress.com)

- Screening out the empathy (theage.com.au)

Humanizing the network

Several years ago now I was working with a team at Yahoo! who were building a platform that automatically surfaced relevant content for visitors to yahoo.com. The engineers were writing algorithms that intended to make the Internet more meaningful to people.

The team eventually worked their way into the Yahoo! home page experience. The Yahoo! home page can reorder content based on what the platform thinks you will most likely click on.

In a sort of similar way, the new Google Instant feature responds to your behaviors and adjusts as you give Google clues as to your intent.

In both cases, the computers help you work less to get what you want faster.

These kinds of innovations are a response to the growth rate of information on the Internet. The big dotcoms need to preserve their position in the market. And it will work to a degree, I’m sure, as the Yahoo!, Google and Facebook infrastructures get so sophisticated that they can’t be beaten at what they do.

But the network is changing shape, and I wonder if these companies are failing to actually evolve with people and the changes happening in society as a result of the presence of this new infrastructure in our world.

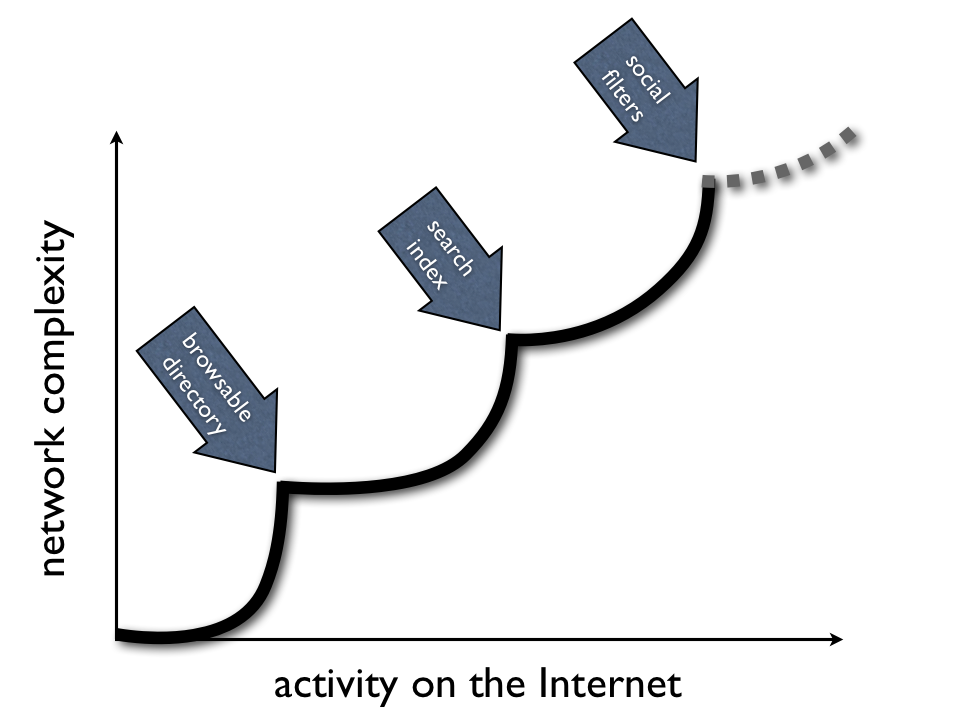

How did we arrive here?

When the world of possibility gets lost in the volume of options people get frustrated. And when people get frustrated technology breakthroughs happen.

This chart shows how certain technological breakthroughs have made the Internet more manageable for people.

In the very early days of the web it was easy enough to find what you wanted just by hopping around from document to document. But it didn’t take long for the world of documents to explode. And when it exploded people became overwhelmed. When they became overwhelmed opportunity opened up to help people get started on their Internet journeys.

The directory took shape, and Yahoo! became the center of the web.

But the directory got full. There was no way to track everything as more and more people arrived and more and more organizations and individuals put more and more documents on the web. The volume of information went through another explosion, and people got frustrated again.

The search game followed, and Google became the center of all things web.

Now, of course, the search engine got full, too. In 2008, Google indexed over 1 trillion documents. The number of searches required to find what you wanted escalated and irritated people. And as the Internet population topped 1 billion people the amount of activity happening online made findability a madhouse again.

People coopted other people to make the Internet feel more human again. The social filter changed the balance of power in our relationship with shared knowledge, and information began to find us.

But this will change, too. Not only will more people join the party, but more networks will get connected and dump large piles of information onto the Internet, not just simple documents. And when real world devices flood the network the connected experience will become overwhelming yet again. Your friends won’t be good enough at helping you to manage your experience.

The new infrastructure

Tom Coates’ recent dConstruct presentation addresses some of this. He says lots of interesting things that anyone making a career developing for the Internet really should hear:

“The increase in transport infrastructure has completely transformed the way we make things and even what we can make….today the history of any object around you is a long and intricate chain of exchange, manufacture, component building, transport. Every object around you implicates the entire planet. Why isn’t the web like that?”

The networked world is still in its infancy, but the many ways we can interleave aspects of our lives with the people and things around us is absolutely incredible. The power people have in their hands is enormous when they know they have it, overwhelming when it discovers them.

With interesting raw data, useful APIs, connected devices and social triggers all around us now the materials to broker and assemble intelligent tools are getting cheaper and easier to offer people. We can devise algorithms that learn and automagically make the nodes on the network more accessible and relevant and valuable to each of us when and where we care about them.

But machines are not great at creating meaning, differentiating emotive responses, interpreting our motivations and contextualizing historical, personal and social references.

Wag the dog

The problem then surfaces when we assume that machines should be doing the hard work of making judgments about things. When machines make lots of small decisions on our behalf we become tempted to let them make the big decisions for us, too.

Amar Bhidé wrote an essay for Harvard Business Review titled “The Judgment Deficit“. He explains how the financial crisis was the result of our willingness to forgo important moral positions because we let machines interpret things humans should be looking at.

“A new form of centralized control has taken root—one that is the work not of old-fashioned autocrats, committees, or rule books but of statistical models and algorithms. These mechanistic decision-making technologies have value under certain circumstances, but when misused or overused they can be every bit as dysfunctional as a Muscovite politburo. Consider what has just happened in the financial sector: A host of lending officers used to make boots-on-the-ground, case-by-case examinations of borrowers’ creditworthiness. Unfortunately, those individuals were replaced by a small number of very similar statistical models created by financial wizards and disseminated by Wall Street firms, rating agencies, and government-sponsored mortgage lenders. This centralization and robotization of credit flourished as banks were freed from many regulatory limits on their activities and regulators embraced top-down, mechanistic capital requirements. The result was an epic financial crisis and the near-collapse of the global economy. Finance suffered from a judgment deficit, and all of us are paying the price.”

The financial meltdown could be interpreted as an autopilot problem, laziness as a result of efficiency. But perhaps even more important than economic catastrophe is the potential for cultural divides to sharpen and even turn violent when people fail to cooperate in healthy ways.

The existence of the network and the machines that make it do wonderful things does not change the fact that we are human, that we can be greedy, cruel, selfish, etc. The network will only amplify the best and worst about humanity.

Ethan Zuckerman woke me up to the important nuances of forming a global society via the Internet in his Activate Summit presentation this summer. The fact that we can communicate with individuals in far away countries, conduct transactions via phone, make goods in one place and ship them from another individually or en masse anywhere in the world does not mean that we understand the people we’re interacting with.

Fish oil, not snake oil

Enabling people to communicate with eachother around the world and to publish on the world’s stage is great. It’s hugely important. As is enabling and incentivizing organizations and institutions to release the raw data that drives what they do. And the many approaches to stitching these things together via infrastructure is a must-have for future generations, as Mr. Coates said.

But we must also learn how to step back and assess the value of the network, the connections happening within and across it. We must learn how to evaluate and articulate what changes need to happen to improve it and our relationship with it.

Without humanizing the decisions that are made as a result of the work computers are doing on our behalf we will be creating crutches for our brains and validating Nick Carr’s fears. Rather than help people take back control of their lives, the technologies will reinforce current power structures and enable new ones that hurt us.

When the next wave of activity on the network renders the social filter unmanageable the technology on the network should respond by empowering individuals and groups to better ourselves and improve global society rather than find more ways for us to do less.

When the next wave of activity on the network renders the social filter unmanageable the technology on the network should respond by empowering individuals and groups to better ourselves and improve global society rather than find more ways for us to do less.

There’s no need to create a new boss that looks just like the old boss. We can do better than that.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Activate 2010: Insights into the web (guardian.co.uk)

- Why the Web Went Wrong: From Self-Organized Swarms to Unruly Flash Mobs (gauravonomics.com)

Publishing network models

There are several ways to think about what publishing networks can be. The models range from a more traditional portfolio of owned and operated properties to loosely connected collections of self-publishing individuals.

Gawker Media is a great example of the O&O portfolio model. Nick Denton recently shared some impressive growth figures across the Gawker family of sites. In total, the network overtook the big US newspaper sites USA Today, Washington Post and LA Times. He’s looking to swim with some bigger fish:

“The newspapers are now the least of our competition. The inflated expectations of investors and executives may one day explode the Huffington Post. And Yahoo and AOL are in long-term decline. But they are all increasingly in our business.”

Gawker owns the content they publish and pays their staff and contributors for their work. The network of sites share a publishing platform but exist independently and serve separate but similar audiences: Jalopnik, Jezebel, Gizmodo, Gawker, Lifehacker and Kotaku.

This model of targeted media properties is what made Pat McGovern so successful with his privately-owned IDG, a global portfolio of 300+ computer-focused magazines and web sites with over $3B in revenue…yes, that’s $3 BILLION!

The Huffington Post has been incredibly successful using the flip-side of Gawker’s model, a decentralized contributor network in addition to a small staff who all post to one media property. Cenk Uygur, host of The Young Turks, mirrors posts from his own site to the Huffington Post web site. He can use the Huffington Post to build his reputation more broadly, and Huffington Post gets some decent coverage to offer their visitors at no cost. He’s had similar success building his brand on YouTube.

Huffington Post has been technically very experimental and innovative, and contributors seem very happy with the results they are getting by posting to the site despite some controversy about not being paid for the value of their work.

Of course, Demand Media is the new Internet publishing posterboy. There’s lots of interesting coverage about what they are up to. Personally, I’m most intrigued by the B2B play they call ‘Content Channels‘. They are getting distribution through other sites such as San Francisco Chronicle and USA Today where they provide Home Guides and Travel Tips, respectively.

Of course, Demand Media is the new Internet publishing posterboy. There’s lots of interesting coverage about what they are up to. Personally, I’m most intrigued by the B2B play they call ‘Content Channels‘. They are getting distribution through other sites such as San Francisco Chronicle and USA Today where they provide Home Guides and Travel Tips, respectively.

The business model is just a very simple advertising revenue sharing agreement. And production costs are kept to a minimum by paying very very low fees for content.

I find WordPress fascinating in this context, too.

It doesn’t make much sense thinking of WordPress.com as a cohesive network except that there’s a single platform hosting each individual blog. The individuals are not connected to each other in any meangingful way, but WordPress has the ability to instrument activities across the network.

A great example of this is when they partnered with content recommendations startup Zemanta to help WordPress bloggers find links and images to add to their posts. There are now thousands of WordPress plugins (including our News Feed plugin) that individual bloggers deploy on their own hosted versions of the platform.

It’s not exactly a self-fueling ecosystem, as there are no revenue models connecting it all together. But it may be the absence of financial shenanigans that makes the whole WordPress ecosystem so compelling to the millions of participants.

Then there’s Glam Media which combines their portfolio of owned and operated properties with a collection of totally independent publishers to create a network. In fact, it’s the independents who actually make up the lionshare of the traffic that they sell.

Glam looks more like an ad network than a more substantive source of interest, but they have done some very clever things. For example, they are developing an application network, a way for advertisers to get meaningful reach for brand experiences that are better than traditional banner ad units. If it works it will create value for everyone in the Glam ecosystem:

“As a publisher, you make money on every ad impression that appears as part of a Glam App. This includes apps embedded on your site and on pop-up pages generated by an application on your site. Glam App ad revenue is split through a three-way rev share between the publisher, app developer, and Glam.”

There’s something very powerful about enabling rich experiences to exist in a distributed way. That was the vision many people shared in terms of the widgetization of the web and a hypersyndication future for media that still needs to happen, in my mind.

At the Guardian we’re balancing a few of these different concepts, as you can see from the Science Blog Network announcement below and our fast-growing Green Network. The whole Open Platform initiative enables this kind of idea, among other things.

There are a few different aspects of the Science Blog Network announcement that are interesting, not least of which is the fact that I was able to post the article directly on my blog here in full using the Guardian’s WordPress plugin.

As Megan Garber of Niemen Journalism Lab said about it…

“The blog setup reframes the relationship between the expert and the outlet — with the Guardian itself, in this case, going from “gatekeeper†to “host.—

The trick that few of the publishing networks have really worked out successfully in my mind is how you surface quality. That’s a much easier problem to solve when your operation is purely owned and operated. But O&O rarely scales as successfully as an open network.

Amar Bhidé wrote a wonderful essay for the September issue of Harvard Business Review about the need for human judgment in a world of complex relationships.

“The right level of control is an elusive and moving target: Economic dynamism is best maintained by minimizing centralized control, but the very dynamism that individual initiative unleashes tends to increase the degree of control needed. And how to centralize—whether through case-by case judgment, a rule book, or a computer model—is as difficult a question as how much.”

At the end of the day it comes down to purpose.

If the intent of the network is purely for generating revenue then it will be susceptible to all kinds of maligned interests amongst participants in the network.

If on the other hand the network is able to create value that the participants actually care about (which should include commercial value in addition to many other measures of value), then the network will have a long growth path and may actually fuel itself over time if it is managed well.

The strategic choices behind the controlled versus open models are very different, and there’s no reason both can’t exist together. What will ultimately matter most is whether or not end-users find value in the nodes of the network.

It’s nearly the end of summer holidays, and there are plans afoot in the blogosphere.

You would not know it from general media coverage but, on the web, science is alive with remarkable debate. According to the Pew Research Centre, science accounts for 10% of all stories on blogs but only 1% of the stories in mainstream media coverage. (The Pew Research Centre’s Project for Excellence in Journalism looked at a year’s news coverage starting from January 2009.)

On the web, thousands of scientists, journalists, hobbyists and numerous other interested folk write about and create lively discussions around palaeontology, astronomy, viruses and other bugs, chemistry, pharmaceuticals, evolutionary biology, extraterrestrial life or bad science. For regular swimmers in this fast-flowing river of words, it can be a rewarding (and sometimes maddening) experience. For the uninitiated, it can be overwhelming.

The Guardian’s science blogs network is an attempt to bring some of the expertise and these discussions to our readers. Our four bloggers will bring you their untrammelled thoughts on the latest in evolution and ecology, politics and campaigns, skepticism (with a dollop of righteous anger) and particle physics (I’ll let them make their own introductions).

Our fifth blog will hopefully become a window onto just some of the discussions going on elsewhere. It will also host the Guardian’s first ever science blog festival – a celebration of the best writing on the web. Every day, a new blogger will take the reins and we hope it will give you a glimpse of the gems out there. If you’re a newbie, we hope the blog festival will give you dozens of new places to start reading about science. And if you’re a seasoned blog follower, we hope you’ll find something entertaining or enraging.

We start tomorrow with the supremely thoughtful Mo Costandi of Neurophilosophy. You can also look forward to posts from Ed Yong, Brian Switek, Jenny Rohn, Deborah Blum, Dorothy Bishop and Vaughan Bell among many others.

In his Hugh Cudlipp lecture in January, Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger discussed the changing relationship between writers (amateur and professional) and readers.

We are edging away from the binary sterility of the debate between mainstream media and new forms which were supposed to replace us. We feel as if we are edging towards a new world in which we bring important things to the table – editing; reporting; areas of expertise; access; a title, or brand, that people trust; ethical professional standards and an extremely large community of readers. The members of that community could not hope to aspire to anything like that audience or reach on their own; they bring us a rich diversity, specialist expertise and on the ground reporting that we couldn’t possibly hope to achieve without including them in what we do.

There is a mutualised interest here. We are reaching towards the idea of a mutualised news organisation.

We’re starting our own path towards mutualisation with some baby steps. We will probably make lots of mistakes (and we know you’ll point them out). Where we end up will depend as much on you as it does on us.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

Related articles by Zemanta

- The Guardian launches science blogs network (blogs.journalism.co.uk)

- Open door: The readers’ editor on… taking up the reins in the age of mutualisation (guardian.co.uk)

- Ex-Times law blogger joins Guardian (guardian.co.uk)

- Guardian to bloggers: please post our content on your blog (econsultancy.com)

How do you visualise the future of datajournalism?

Following the big rules of datajournalism can take you to some strange places. What are the big three?

1) Everything is data

2) If you can get the data, then you can visualise it

3) Just because it is data doesn’t mean it it isn’t subjective

These were put to the test at the recent European Centre of Journalism’s data conference in Amsterdam. Graphic artist Anna Lena Schiller took each talk at the event and visualised it while it was going on. You can see mine here and Tony Hirst’s here. The full set is above.

On her blog, Anna Lena explains:

The day was divided into four parts, with two to five ten minute talks in each session. When you browse through the pictures you’ll see the headlines, participants and topics of the talks.

Anna Lena has also been working on the big meet up in Berlin this week at which my colleague Martin Belam spoke – so soon we’ll get to see what she made of that event.

World government data

• Search the world’s government datasets

• More environment data

• Get the A-Z of data

• More at the Datastore directory

• Follow us on Twitter

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Data Journalism: the View from Europe (programmableweb.com)

- Why the US and UK are leading the way on semantic web (blogs.journalism.co.uk)

- Data and its impact on journalism (flowingdata.com)

Captivating Arcade Fire video shows what HTML5 can do

This is a wonderful interactive…a must-see: http://www.thewildernessdowntown.com/

It keeps crashing on me, but I’ve had enough of a blast to be inspired – it’s the heavenly Arcade Fire video built in collaboration with Google and director Chris Milk.

The Wilderness Downtown combines Arcade Fire’s We Used To Wait with some beautiful animation and footage – courtesy of Street View – of your childhood home – made all the more poignant for me because it was bulldozed a few years ago.

Thomas Gayno from Google’s Creative Labs decsribed it on the Chrome Blog: "It features a mash-up of Google Maps and Google Street View with HTML5 canvas, HTML5 audio and video, an interactive drawing tool, and choreographed windows that dance around the screen. These modern web technologies have helped us craft an experience that is personalised and unique for each viewer, as you virtually run through the streets where you grew up."

The Chrome Experiments blog explains each technique, including the flock of birds that respond to the music and mouse movemens, created with the HTML5 Canvas 3D engine, film clips played in windows at custom sizes, thanks to HTML5, and various colour correction, drawing and animation techniques.

I’ve watched thousands of videos thanks to the curse of the viral video chart and nothing has come close to this for originality, imagination and for that inspired piece of personalised storytelling.

There’s plenty more inspiration on the Chrome Experiments blog; Bomomo is pretty slick, and Canopy is hypnotic.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

Related articles by Zemanta

- What do Arcade Fire and HTML5 have in common? (googlecode.blogspot.com)

Read this! Gmail now prioritises your inbox

Gmail’s latest feature is arguably the biggest innovation since the service launched in April 2004.

‘Priority inbox’ learns from your email usage patterns and begins to prioritise messages that it thinks you’ll be most likely to read. Your inbox is divided into three sections: important and unread, starred and everything else.

The classification should improve, because you can mark messages with ‘less important’ or ‘more important’, and Gmail will learn to reclassify accordingly. It’s like the inverse of junk mail filtering.

Software engineer Doug Aberdeen on the official Gmail blog described this as “a new way of taking on information overload”.

“Gmail uses a variety of signals to predict which messages are important, including the people you email most (if you email Bob a lot, a message from Bob is probably important) and which messages you open and reply to (these are likely more important than the ones you skip over).”

Priority inbox is slowly rolling out across Gmail services. It hasn’t appeared in my personal account yet, but will in the next few days along with Google Apps users (if their administrator has opted to ‘Enable pre-release features’).

Drag and drop, launched in April, helped a little. Filters help, for those that can be bothered to set them up. But priority inbox could make a significant difference, and if Wave wasn’t quite the right format for centralising and streamlining messages, then this is a more usable step in that direction.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Email overload? Try Priority Inbox (googleblog.blogspot.com)

Paper.li: Guardian Technology – now available as a newspaper, online!

Taking the feeds and links we follow online and reformatting them in a print format seemed a gimmick to start with. But part of the pleasure of print is a linear reading experience; there’s a beginning and an end, and a satisfaction from feeling you’ve read everything that matters at one point in time.

Paper.li, Twitter Tim.es and Flipboard all appeal to our sense of nostalgia, but also perhaps our feeling of being overwhelmed by the volume of content we are faced with each day. Filtering has never been more important.

Coming back to the idea of an editorial package that’s fixed at one point in the day, we’ve put together a Paper.li for Guardian technology. A newspaper with a technology section drops the technology section to focus on the website, which then publishes a digital newspaper made up from feeds of technology news. Got that? If you’re really lucky, you’ll get a side order of Google ad for Guardian newspaper subscriptions too. Would you like a little extra irony with that, madam?

Let us know how useful it is, if it is.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

Video highlights from Activate 2010

The team here has begun posting the videos from Activate 2010. What an inspiring day.

Here is the highlight reel: