The following article first appeared on Contributoria.com, the community funded collaborative journalism platform.  It was also published by The Guardian.

In theory, press freedom and the commercial markets should be fantastic partners on the internet. These two forces are better because of each other than either one is alone.

It’s not always a healthy marriage, though.

The mutually beneficial dynamic that many collectivist and individualist forces have worked out together on the internet today works more like a mutually exclusive dynamic between press freedom and commercial interests.

They often operate independently of each other when they could both benefit from investing in the partnership.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss

Traditionally, financial control of a newspaper in the hands of a wealthy individual, family or shareholders has supported newspapers very effectively and for a long time. This model has existed since the beginning of the business of journalism, and it has also allowed newcomers to enter the market and either support older businesses (Jeff Bezos’ purchase of the Washington Post) or create new businesses (Pierre Omidyar’s launch of New Look Media).

Yet the internet is particularly good at distributing influence and democratising voices in a very egalitarian way. The same can’t always be said about the platforms that operate on the internet, which sometimes have more hierarchical models, but the technology and user behaviours are capable of supporting independent media if the support model is applied well.

While a patriarch may protect press freedom, it comes with strings attached. There are better options.

Best friends forever

Of course, advertising is a working model. There’s a massive and very mature marketplace operating today and both sides of the equation understand each other well. Journalism and advertising are best friends forever on the internet.

In fact, the traditional news outlets are getting smarter about making the advertising vehicles they offer mutually beneficial for the advertiser, the media owner and the end user alike. One of the best examples of that model playing out is GuardianWitness, a user-contribution platform where the sponsor was a collaborator in the creation of the product.

However, advertisers are finding their customers through other channels, too. Everyone is a publisher on the internet, including advertisers. And the wider selection of options across the media landscape means news organisations need to work a lot harder to retain those relationships.

While functionally serviceable, the press freedom and advertising relationship is mostly platonic. The internet is capable of delivering much more value at scale than what’s happening today.

Taking back control

While the dotcom giants of Silicon Valley created new power structures and operating rules over the last several years, the incumbent media forces held their ground, watched and waited to see how big the opportunity would get. By moving slowly they eventually learned how to benefit from not playing by the rules.

For example hiding your website behind a paywall, where Google can’t find you, and focusing the attention of your readers on a direct and explicit transactional relationship instead of syphoning them off Facebook is an interesting way to protect your revenues from going elsewhere. After all, the argument goes, readers should be paying for the quality journalism they are reading. It’s simple logic.

Simple answers aren’t going to solve the problem, though. As FT columnist John Grapper tweeted, “I find the argument that people ‘should’ pay for news as flawed as the claim that it ‘should’ be free.”

Mathew Ingram a journalist covering the media business at GigaOm suggests the paywall is too blunt and fails to respect the relationship the reader wants to have with the media. “The paywall is undifferentiated. It gets applied across everything the newspaper produces and forces people to pay whether they want to or not. On the other hand, with a subscription model like Andrew Sullivan’s (The Daily Dish) you know exactly what you’re getting. It comes down to the question, ‘Do your interests align with the creator?’ In that sense Andrew Sullivan’s is a very personalised paywall.”

The paywall business model may in fact define the value of the business to its readers, but it doesn’t value the impact of the story in the world. It protects the existence of the business first and foremost, a choice many newspapers have decided justifies the costs of being less accessible to the world’s media distribution channels.

Rather than joined up in a healthy and supportive partnership, one side is always subservient to the other side in these relationships, an unhealthy long-term agreement regardless of which side thinks it is in control.

An open relationship

Newspapers can learn a lot from open publishing platforms which fuel mutually beneficial relationships between the producer, the host, advertisers and the consumer.

WordPress, for example, is host to over 75m blogs in the world today. It not only hosts websites for free, it licenses its software openly, too – the source code itself. WordPress makes money by selling premium services to those who need more support.

Newspapers face additional costs as a result of the hands-on role they take in paying for, crafting and selecting individual articles. They have civic responsibilities to respect certain institutions, industry codes of conduct such as commitments to accuracy and privacy standards, political influences including prior restraint laws and regulatory bodies, and cultural expectations, which vary from country to country.

The open content host or open distribution model can be too risky for the stable and nurturing relationship that press freedom seeks sometimes, but there are some interesting examples that begin to blend these two worlds and create mutually beneficial relationships that are worth watching closely, including Daily Kos, the New Jersey News Commons and Global Voices, to name a few.

What’s mine is yours

There may yet be an answer in generative platforms, a more purely and intrinsically internet-native model that leverages the natural give-and-take relationship the internet fosters so effectively.

The ideal system would fuel growth by building value collectively as a result of serving the needs of the individual.

When it works it can snowball and develop into what is known as a network effect. These platforms generate value as more participants join and become active across the system.

A generative business model fuelling the operational requirements of investigative journalism would be a powerful innovation indeed. With democratic commissioning on one side and self-serve licensing and open distribution on the other, the journalist could sit in the middle and manage their own relationship to multiple funding channels.

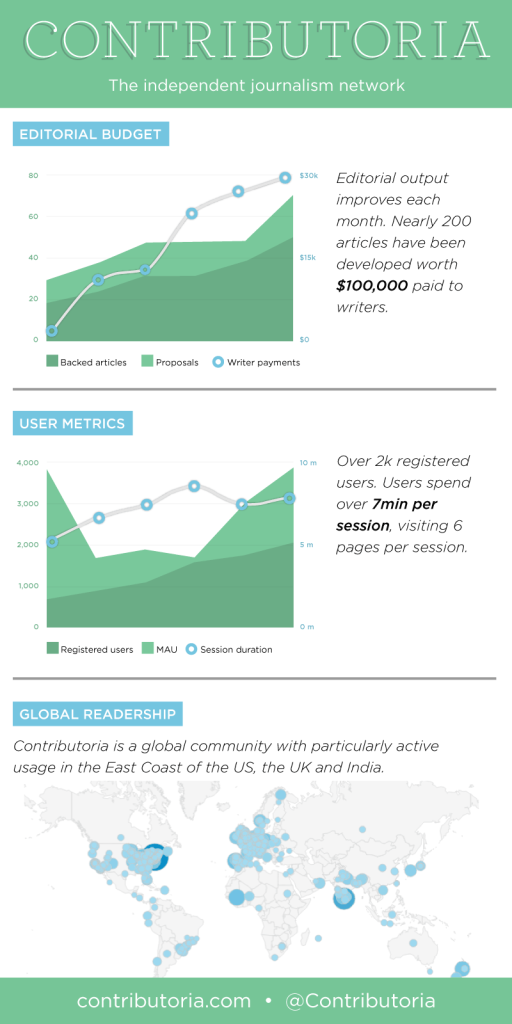

Notwithstanding Contributoria’s mission to support journalism in precisely this way, to date, a two-sided platform for journalism has yet to be applied at scale.

Til death do us part

Of the many revolutionary developments the internet has inspired, the most important might be the recalibration of social good and self-interest as congruous forces.

Perhaps this union comes from way down at the deepest layers of the internet’s protocols where give-and-take goes in both directions in a very literal sense. Perhaps it’s the limitless nature of the space we’re creating and a natural human desire to work together to shape it.

Whatever the reason, we’ve become incredibly effective at using the internet to barter, to share resources, and to collaborate on the creation of things. The result of this approach is that communities are benefiting as a whole as a direct result of fulfilling the needs of the individual.

The details of the relationship may be difficult to work through and require more compromise and sometimes even sacrifice than either side may prefer, but the right relationship is always worth fighting for even when times get tough – particularly when it comes to ideals as important as press freedom and trade.