One of the things that fascinates me about the whole mobile and social media landscape is the increasing importance the physical world plays in our digital experience and vice versa.

The devices are binding the physical and networked worlds and changing the shape of markets and social institutions.

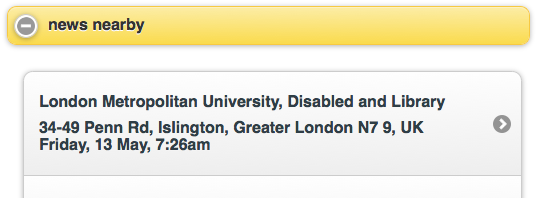

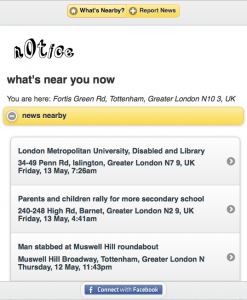

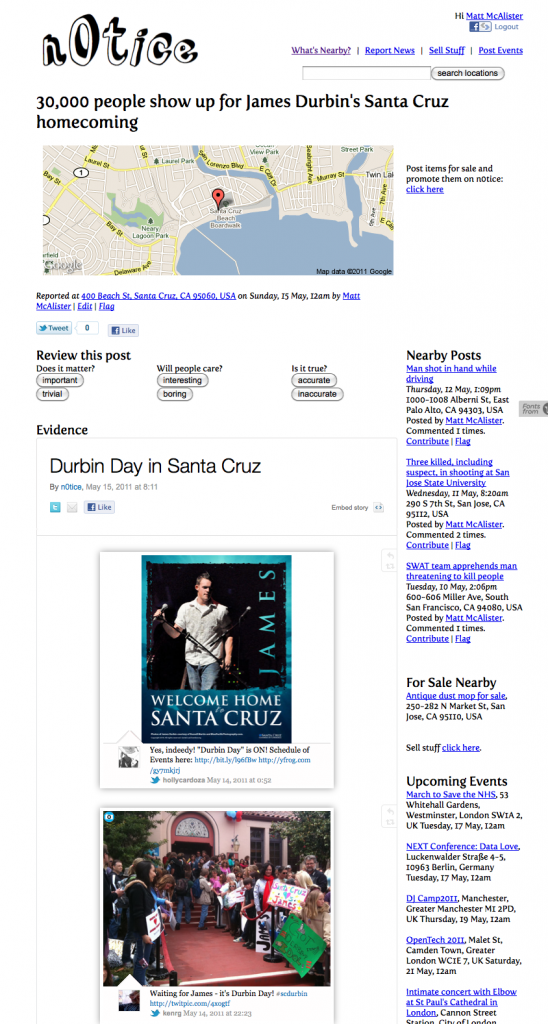

I’ve become more interested in this because of n0tice.com, a new twist on a very old idea – the public noticeboard.

Many have considered technological convergence long before now. Marshall MacLuhan was one of the more articulate voices of this particular concept way back in the 1960’s.

More recently Google’s founders wanted their company to be the force that united the digital network with the physical world…this is a quote from Larry Page in 2004:

“Ultimately I view Google as a way to augment your brain with the knowledge of the world. Right now you go into your computer and type a phrase, but you can imagine that it could be easier in the future, that you can have just devices you talk into, or you can have computers that pay attention to what’s going on around themâ€

On the surface this binding effect may appear to be a simple and obvious evolution of technology we know and understand already, but the broader impact of the change feels bigger than the sum of its parts:

- First, there are, of course, the devices themselves, the point of contact. This is what we use to physically engage. The change we’re going through right now may not feel as different as the step we took from TV to PC, but you can imagine the step from PC to mobile device may feel even more dramatic in a few years…particularly as tiny sensors become like dust around us everywhere all the time.

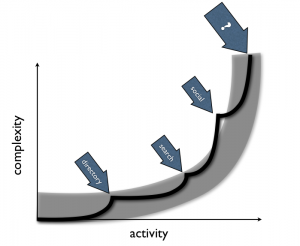

- Then we can see innovations in the interfaces sitting on top of those devices. New OSes, browsers and apps – a whole software movement is accelerating via the unique capabilities of the devices and our relationships with them. The ones we see and use are the human to machine experiences, but there are also many automated machine-to-machine interfaces that we don’t even know are happening.

- The information flow as it extends into this new space has a different feel to it, a different utility, a different role in our lives. Much like TV started as radio programs on camera, many early mobile experiences are web sites on small browsers. That is changing fast as the mobile pure plays catch their stride. The digital incumbents have a long journey ahead of them still, but they are no longer sleepwalking into it and will surely get there soon.

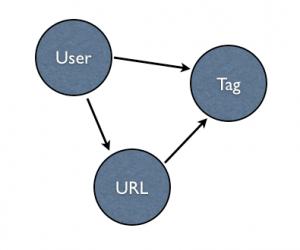

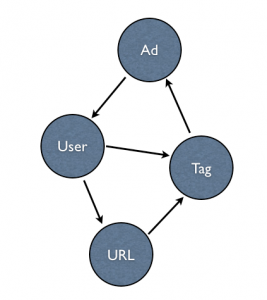

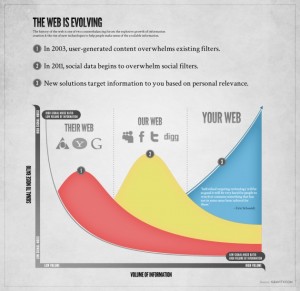

- Lastly, the shape of the information itself is becoming increasingly atomized. It seems obvious how information is changing when you consider the more recent proliferation of microblogging and data journalism, but most people don’t realize the depth of knowledge forming beneath the surface. We’re probably not as conscious as we should be about the way different platforms extract knowledge about each of us from looking at the data exhaust we leave when we move around the network.

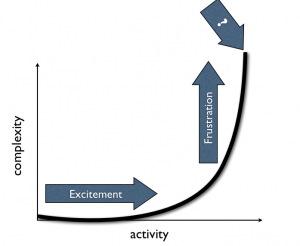

So, the ‘stack’, if you want to call it that, doesn’t feel totally foreign if you were paying attention during the first wave or two of network activity, but that’s only because it’s so early still.

Another way to look at the change is through Kevin Kelly’s eyes, which is always a smart thing to do. He describes the large-scale trends using the verbs: Screening, Interacting, Sharing, Flowing, Accessing, Generating

I’m particularly interested in the generative ideas he mentions here. I wrote a long form paper about that titled ‘Generative Media Networks.’

Many others have been talking about the movement toward the Internet of things:

“Fridges, buses and buildings will be able to share data and adapt to suit our needs. In fact, Cisco estimates that the number of “things” connected to the internet has already surpassed the number of people on earth.â€

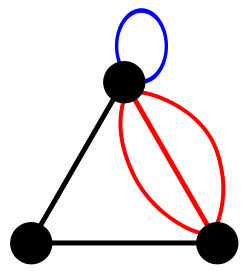

And one more approach to defining the broader trend comes from Tom Coates. Â He developed a really nice visual way to describe some what’s happening in his presentation Everything the Network Touches:

Now, where things start to get interesting and make me think about the size of the opportunity ahead is when you realize how explicit and direct the network’s role is becoming in our lives. This is very different from Web 1.0 and 2.0.

The network is no longer a thing you spend time on. It doesn’t compete with other media sources for your attention, because it’s always there. Your attention to it is a matter of focus and intent, less of an on/off switch.

The network is no longer something you can only use when you’re sitting at a desk. You don’t have to go somewhere to get on it. It’s on you instead.

The network is increasingly becoming an extension of what we are thinking and doing, when and wherever we are thinking and doing it.

But perhaps most importantly, and this is where things really feel different from the PC-and-browser era, there’s a two-way bi-directional relationship with the network.

Sure, we had a person-to-person bi-directional network before the mobile era. But email, IM and social networking had to be triggered and engaged before it started working.

In the new physical-digital network era, the network can do things for us just by taking some context from the devices and software that are connected to us.

Gary Wolf explains one outcome of this binding effect in his TED talk on “The Quantified Selfâ€.  He is referring to the many ways in which people are tracking their daily behaviors to understand more about themselves.

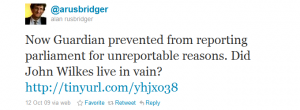

There was a word used a lot to characterize the way people and organizations need to behave in a connected world – ‘transparency’.

That was once just a thing people said, mostly frivolously, but now the scale of that truth is almost overwhelming.

It seems to me that we’ve barely scratched the surface, that the word ‘transparency‘ as we apply it today is going to feel like a toddler when this megatrend matures and we all fully embrace the externalization of our personal behaviors and social institutions.

For example, David Weinberger recently demontrated how the externalisation of the journalistic process is playing out on Reddit, in particular around their IAMA and TIL threads:

“it’s not exactly 60 Minutes. So what? This is one way citizen journalism looks. At its best, it asks questions we all want asked, unearths questions we didn’t know we wanted asked, asks them more forthrightly than most American journalists dare, and gets better — more honest — answers than we hear from the mainstream media.â€

In a much more extreme case, the government of Iceland is being externalized through a collaborative rewrite of their constitution:

“A group of 25 citizens presented a draft of the constitution to Iceland’s parliament. The group, which is made up of ordinary residents, compiled the document online with the help of hundreds of others. The constitution council posted the first draft in April on its website and then let citizens comment via a Facebook Page. The council members are also active on Twitter, post videos of themselves on YouTube and put pictures on Flickr.”

It’s wonderful to see how important people’s voices have become to the fabric of the network.

In the Web 2.0 world we had a name for participation: ‘user generated content‘ or ‘UGC‘. While many recognized UGC was a terrible thing to call this new activity, people had no choice but to articulate the new thing in a way that those who didn’t participate online could understand.

In this new world, there’s no name for the stuff people contribute. It’s a redundant concept.

That is part of the inspiration for n0tice.com. I want to externalize all the constructs that shape a fact. Â What would an information network look like if Richard Rogers were to architect it using the materials who, what, where and when?

It’s also the basis for another project we are working on around creative collaboration. Can creativity be flattened further so that it’s more accessible to a broader public? Can the commissioner be the commissioned?

I consistently find myself wanting to flip every problem around and to expose the systems and processes behind it. Everything gets filtered through the same lens: “What would happen if you turned it all upside down and inside out? Why can’t the seller be the buyer or the consumer be the producer? Is there a way to flatten the control structure and make the solution to the problem more accessible to more participants?  Can the solution generate new activities that form something better?”

While it doesn’t always help to reduce many important changes to a single concept, the world looks very different to me when viewed this way.

Humanity is becoming externalized, shaped by a binding effect between the digital and physical worlds, fuelled by the growth of generative media platforms.

Hopefully, I’ll be able to demonstrate what this actually means in reality and show how it can work soon.

There are many approaches to playing in this space. Â The important thing is to be in it and to actually do something about it.

Stay tuned…