Cory is spot on, as usual.

This article titled “The real cost of free” was written by Cory Doctorow, for theguardian.com on Tuesday 5th October 2010 11.06 UTC

This article titled “The real cost of free” was written by Cory Doctorow, for theguardian.com on Tuesday 5th October 2010 11.06 UTC

Last week, my fellow Guardian columnist Helienne Lindvall published a piece headlined The cost of free, in which she called it "ironic" that "advocates of free online content" (including me) "charge hefty fees to speak at events".

Lindvall says she spoke to someone who approached an agency I once worked with to hire me for a lecture and was quoted ,000-,000 (£6,300-£12,700) to speak at a college and ,000 to speak at a conference. Lindvall goes on to talk about the fees commanded by other speakers, including Wired editor Chris Anderson, author of a book called "Free" (which I reviewed here in July 2009), Pirate Bay co-founder Peter Sunde and marketing expert Seth Godin. In Lindvall’s view, all of us are part of a united ideology that exhorts artists to give their work away for free, but we don’t practice what we preach because we charge so much for our time.

It’s unfortunate that Lindvall didn’t bother to check her facts. I haven’t been represented by the agency she referenced for several years, and in any event, no one has ever paid me ,000 to appear at any event. Indeed, the vast majority of lectures I give are free (see here for the past six months’ talks and their associated fees – out of approximately 95 talks I’ve given in the past six months, only 11 were paid, and the highest paid of those was £300). Furthermore, I don’t use an agency for the majority of my bookings (mostly I book myself – I’ve only had one agency booking in the past two years). I’m not sure who the unfortunate conference organiser Lindvall spoke to was – Lindvall has not identified her source – but I’m astonished that this person managed to dig up the old agency, since it’s not in the first 400 Google results for "Cory Doctorow".

It’s true that my stock response to for-profit conferences and corporate events is to ask for ,000 on the grounds that almost no one will pay that much so I get to stay home with my family and my work; but if anyone will, I’d be crazy to turn it down. Even so, I find myself travelling more than I’d like to, and usually I’m doing so at a loss.

Why do I do this? Well, that’s the bit that Lindvall really got wrong.

You see, the real mistake Lindvall made was in saying that I tell artists to give their work away for free. I do no such thing.

The topic I leave my family and my desk to talk to people all over the world about is the risks to freedom arising from the failure of copyright giants to adapt to a world where it’s impossible to prevent copying. Because it is impossible. Despite 15 long years of the copyright wars, despite draconian laws and savage penalties, despite secret treaties and widespread censorship, despite millions spent on ill-advised copy-prevention tools, more copying takes place today than ever before.

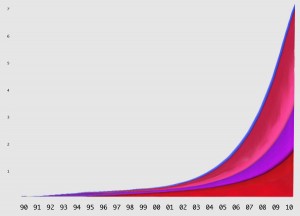

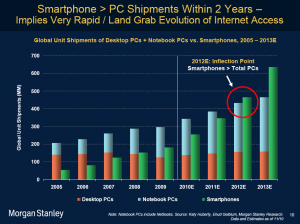

As I’ve written here before, copying isn’t going to get harder, ever. Hard drives won’t magically get bulkier but hold fewer bits and cost more.

Networks won’t be harder to use. PCs won’t be slower. People won’t stop learning to type "Toy Story 3 bittorrent" into Google. Anyone who claims otherwise is selling something – generally some kind of unworkable magic anti-copying beans that they swear, this time, will really work.

So, assuming that copyright holders will never be able to stop or even slow down copying, what is to be done?

For me, the answer is simple: if I give away my ebooks under a Creative Commons licence that allows non-commercial sharing, I’ll attract readers who buy hard copies. It’s worked for me – I’ve had books on the New York Times bestseller list for the past two years.

What should other artists do? Well, I’m not really bothered. The sad truth is that almost everything almost every artist tries to earn money will fail. This has nothing to do with the internet, of course. Consider the remarkable statement from Alanis Morissette’s attorney at the Future of Music Conference: 97% of the artists signed to a major label before Napster earned 0 or less a year from it. And these were the lucky lotto winners, the tiny fraction of 1% who made it to a record deal. Almost every artist who sets out to earn a living from art won’t get there (for me, it took 19 years before I could afford to quit my day job), whether or not they give away their work, sign to a label, or stick it through every letterbox in Zone 1.

If you’re an artist and you’re interested in trying to give stuff away to sell more, I’ve got some advice for you, as I wrote here – I think it won’t hurt and it could help, especially if you’ve got some other way, like a label or a publisher, to get people to care about your stuff in the first place.

But I don’t care if you want to attempt to stop people from copying your work over the internet, or if you plan on building a business around this idea. I mean, it sounds daft to me, but I’ve been surprised before.

But here’s what I do care about. I care if your plan involves using "digital rights management" technologies that prohibit people from opening up and improving their own property; if your plan requires that online services censor their user submissions; if your plan involves disconnecting whole families from the internet because they are accused of infringement; if your plan involves bulk surveillance of the internet to catch infringers, if your plan requires extraordinarily complex legislation to be shoved through parliament without democratic debate; if your plan prohibits me from keeping online videos of my personal life private because you won’t be able to catch infringers if you can’t spy on every video.

And this is the plan that the entertainment industries have pursued in their doomed attempt to prevent copying. The US record industry has sued 40,000 people. The BBC has received Ofcom’s approval to use our mandatory licence fees to lock up its broadcasts with DRM so that we can’t tinker with or improve on our own TVs and recorders (and lest you think that this is no big deal, keep in mind that the entire web was created by amateurs tinkering with systems around them). What’s more Apple, Audible, Sony and others have stitched up several digital distribution channels with mandatory DRM requirements, so copyright holders don’t get to choose to make their works available on equitable terms.

In France, the HADOPI "three strikes" rule just went into effect; they’re sending out 10,000 legal threats a week now, and have promised 150,000 a week in short order. After three unsubstantiated accusations of infringement, your whole family is disconnected from the internet – from work, education, civic engagement, distant relatives, health information, community. And of course, we’ll have the same regime here shortly, thanks to the Digital Economy Act, passed in a three-whip wash-up in the last days of parliament without any substantive debate, despite the thousands and thousands of Britons who asked their legislators to at least discuss this extraordinarily technical legislation before passing it into law.

Viacom is just one of the many entertainment giants suing companies like Google for allowing everyday people to upload content to the internet without reviewing its copyright status in advance. Never mind that there’s 29 hours of video uploaded to YouTube every minute, that there aren’t enough lawyers in all the world to undertake such a review, and that throttling the videos (by charging uploaders for legal review, for example) would put practically every person who finds in YouTube the opportunity for personal and creative expression out of business.

Never mind that if this principle were passed into law, it would shutter every message board, Twitter, social networking service, blog, and mailing list in a second. That’s bad enough, but in addition to these claims, Viacom has asked the court to order Google to make all user-uploaded content public so that Viacom can check it doesn’t infringe copyright – it thinks that its need to look at my videos is greater than my need to, say, flag a video of my two-year-old in the bath as private and visible only to me and her grandparents.

Meanwhile, the entertainment industries continues their push around the world for a series of China-style national firewalls (in the UK, former BPI executive Richard Mollet boasted of getting this legislation inserted into the Digital Economy Act).

This is an approach that millionaire pop stars like U2’s Bono wholeheartedly endorse – last Christmas, he penned a New York Times op-ed calling for Chinese-style censorship everywhere. And just this month, MPAA representatives told the world’s governments that adopting national internet censorship regimes for copyright would also allow them to block information embarrassing to their regimes, such as WikiLeaks.

The MPAA was addressing a meeting for the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, a secret treaty that is being negotiated away from the UN, behind closed doors, and which includes proposals to search iPods, phones and laptop hard-drives at the world’s borders to look for infringement.

So yeah, if you want to try to control individual copies of your work on the internet, go ahead and try. I think it’s a fool’s errand, and so does almost every technical expert in the world, but what do we know?

But for so long as this plan involves embedding control, surveillance and censorship into the very fabric of the information society’s infrastructure, I’ll continue to tour the world, for free, spending every penny I have and every ounce of energy in my body to fight you.

Helienne, I can’t fault you for not reading my Guardian columns; after all, I’ve never read yours. And while I do fault you for not correcting the record, I won’t ask the Guardian’s reader’s editor to intervene or make silly, chiropractor-esque noises about libel. I’m a civil libertarian, and I have integrity, and I believe that the answer to bad speech is more speech, hence this column.

But you really ought to familiarise yourself with the ideologies of the people you’re condemning before you tear into them. I don’t agree with everything Chris Anderson says, but he hardly tells people to give their stuff away: mostly, Chris talks about how different pricing structures, loss-leaders, and sales techniques can be used to increase the bottom lines of creators, manufacturers, publishers and inventors, and he cites case studies of people who’ve made this work for them.

I have no idea what Seth Godin is doing on your hitlist: Seth’s a marketing consultant. The last three times I’ve heard him speak, he’s been talking about how to improve corporate communications and brand identity – that sort of thing. Sure, he apparently charges a very large sum of money for this advice, but that’s the topsy-turvy world of marketing for you. If your point is that creative people deserve to get paid, then presumably you’re all for Seth charging whatever the market will bear.

Now, Peter Sunde is an interesting case. He really does advocate something like totally unrestricted copying. But as you note yourself, this is a belief that he’s prepared to go to jail for, which is generally considered the gold standard for sincerity (the only higher standard I know of is being prepared to die for your beliefs – you should ask Peter where he stands on this). If your point is that Peter is only shamming about his politics, how do you explain this willingness to be imprisoned for them? Also: given Peter’s latest startup, Flattr, exists for the sole purpose of making it simple for audiences to pay artists, I think you might reconsider his place in your parade of villainy.

I understand perfectly well what you’re saying in your column: people who give away some of their creative output for free in order to earn a living are the exception. Most artists will fail at this. What’s more, their dirty secret is their sky-high appearance fees – they don’t really earn a creative living at all. But authors have been on the lecture circuit forever – Dickens used to pull down 0,000 for US lecture tours, a staggering sum at the time. This isn’t new – authors have lots to say, and many of us are secret extroverts, and quite enjoy the chance to step away from our desks to talk about the things we’re passionate about.

But you think that anyone who talks up their success at giving away some work to sell other work is peddling fake hope. There may be someone out there who does this, but it sure isn’t me. As I’ve told all of my writing students, counting on earning a living from your work, no matter how you promote it or release it, is a bad idea. All artists should have a fallback plan for feeding themselves and their families. This has nothing to do with the internet – it’s been true since the days of cave paintings.

You know who peddles false hope to naive would-be artists? People who go around implying that but for all those internet pirates, there’d be full creative employment for all of us. That the reason artists earn so little is because our audiences can’t be trusted, that once we get this pesky internet thing solved, there’ll be jam tomorrow for everyone. If you want to damn someone for selling a bill of goods to creative people, go after the DRM vendors with their ridiculous claims about copy-proof files; go after the labels who say that wholesale lawsuits against fans on behalf of artists (where labels get to pocket the winnings) are good business; go after the studios who are suing to make it impossible for anyone to put independent video on the internet without a giant corporate legal budget.

And if you want to find someone who supports artists, look at organisations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who have advanced the cause of blanket licences for music, video and other creative works on the internet. As a songwriter, you’ll be familiar with these licences: as you say, you get 3% every time someone performs your songs on stage. What EFF has asked for is the same deal for the net: let ISPs buy blanket licences on behalf of their customers, licences that allow them to share all the music they’re going to share anyway – but this way, artists get paid. Incidentally, this is also an approach favored by Larry Lessig, whom you also single out as "ironic" in your piece.

It’s been 15 years since the US National Information Infrastructure hearings kicked off the digital copyright wars. And for all the extraordinary power grabbed by the entertainment giants since then, the letters of marque and the power to disconnect and the power to censor and the power to eavesdrop, none of it is paying artists. Those who say that they can control copies are wrong, and they will not profit by their strategy. They should be entitled to ruin their own lives, businesses and careers, but not if they’re going to take down the rest of society in the process.

And that, Helienne, is what I tell people when I give my lectures, whether paid or free.

<a href="http://oas.theguardian.com/RealMedia/ads/click_nx.ads/guardianapis.com/technology/oas.html/@Bottom" rel="nofollow"> <img src="http://oas.theguardian.com/RealMedia/ads/adstream_nx.ads/guardianapis.com/technology/oas.html/@Bottom" alt="Ads by The Guardian" /> </a>

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.