I wrote this piece for the Guardian’s Media Network on the role that RSS could play now that the social platforms are becoming more difficult to work with. GeoRSS, in particular, has a lot of potential given the mobile device explosion. I’m not suggesting necessarily that RSS is the answer, but it is something that a lot of people already understand and could help unify the discussion around sharing geotagged information feeds.

While the news that Twitter will no longer support RSS was not really surprising, it was a bit annoying. It served as yet another reminder that the Twitter-as-open-message-utility idea that many early adopters of the service loved was in fact going away.

There are already several projects intending to disrupt Twitter, mostly focused on the idea of a distributed, federated messaging standard and/or platform. But we already have such a service: an open standard adopted by millions of sources; a federated network of all kinds of interesting, useful and entertaining data feeds published in real-time. It’s called RSS.

There was a time when nearly every website was RSS-enabled, and a cacophony of Silicon Valley startups fought to own pieces of this new landscape, hoping to find dotcom gold. But RSS didn’t lead to gold, and most people stopped doing anything with it.

Nobody found an effective advertising or service model (except, ironically, Dick Costolo, CEO of Twitter, who sold Feedburner to Google). The end-user market for RSS reading never took off. Media organisations didn’t fully buy into it, and the standard took a backseat to more robust technologies.

Twitter is still very open in many ways and encourages technology partners to use the Twitter API. That model gives the company much more control over who is able to use tweets outside of the Twitter owned apps, and it’s a more obvious commercial strategy that many have been asking Twitter to work on for a long time now.

But I think we’ve all made a mistake in the media world by turning our backs on RSS. It’s understandable why it happened. But hopefully those who rejected RSS in the past will see the signals demonstrating that an open feed network is a sensible thing to embrace today.

Let’s zoom out for context first. Looking at the macro trends in the internet’s evolution, we can see one or two clear winners as more information and more people appeared on the network in waves over the last 15 years.

Following the initial explosion of new domains, Yahoo! solved the need to surface only the websites that mattered through browsing. The Yahoo! directory became saturated, so Google then surfaced pages that mattered within those websites through searches. Google became saturated, so Facebook and Twitter surfaced things that mattered that live on the webpages within those web sites through connecting with people.

Now that the social filter is saturated, what will be used next to surface things that matter out of all the noise? The answer is location. It is well understood technically. The software-hardware-service stack is done. The user experience is great. We’re already there, right?

No – most media organisations still haven’t caught up yet. There’s a ton of information not yet optimised for this new view of the world and much more yet to be created. This is just the beginning.

Do we want a single platform to be created that catalyses the location filter of the internet and mediates who sees what and when? Or do we want to secure forever a neutral environment where all can participate openly and equally?

If the first option happens, as historically has been the case, then I hope that position is taken by a force that exists because of and reliant on the second option.

What can a media company do to help make that happen? The answer is to mobilise your feeds. As a publisher, being part of the wider network used to mean having a website on a domain that Yahoo! could categorise. Then it meant having webpages on that website optimised for search terms people were using to find things via Google. And more recently it has meant providing sharing hooks that can spread things from those pages on that site from person to person.

Being part of the wider network today suddenly means all of those things above, and, additionally, being location-enabled for location-aware services.

It doesn’t just mean offering a location-specific version of your brand, though that is certainly an important thing to do as well. The major dotcoms use this strategy increasingly across their portfolios, and I’m surprised more publishers don’t do this.

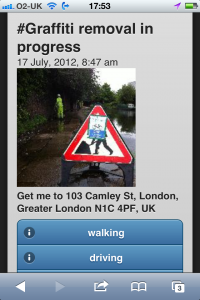

More importantly, though, and this is where it matters in the long run, it means offering location-enabled feeds that everyone can use in order to be relevant in all mobile clients, applications and utilities.

Entrepreneurs are all over this space already. Pure-play location-based apps can be interesting, but many feel very shallow without useful information. The iTunes store is full of travel apps, reference apps, news, sports, utilities and so on that are location-aware, but they are missing some of the depth that you can get on blogs and larger publishers’ sites. They need your feeds.

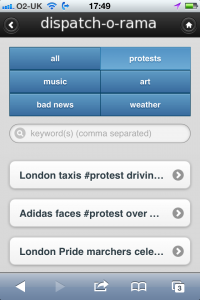

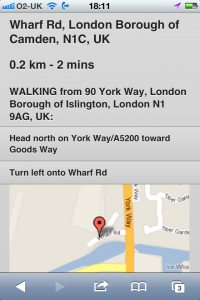

Some folks have been experimenting in some very interesting ways that demonstrate what is possible with location-enabled feeds. Several mobile services, such as FlipBoard, Pulse and now Prismatic, have really nice and very popular mobile reading apps that all pull RSS feeds, and they are well placed to turn those into location-based news services.

Perhaps a more instructive example of the potential is the augmented reality app hypARlocal at Talk About Local. They are getting location-aware content out of geoRSS feeds published by hyperlocal bloggers around the UK and the citizen journalism platform n0tice.com.

But it’s not just the entrepreneurs that want your location-enabled feeds. Google Now for Android notifies you of local weather and sports scores along with bus times and other local data, and Google Glasses will be dependent on quality location-specific data as well.

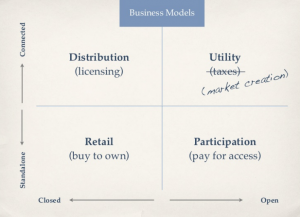

Of course, the innovations come with new revenue models that could get big for media organisations. They include direct, advertising, and syndication models, to name a few, but have a look at some of the startups in the rather dense ‘location‘ category on Crunchbase to find commercial innovations too.

Again, this isn’t a new space. Not only has the location stack been well formed, but there are also a number of bloggers who have been evangelising location feeds for years. They already use WordPress, which automatically pumps out RSS. And many of them also geotag their posts today using one of the many useful WordPress mapping plugins.

It would take very little to reinvigorate a movement around open location-based feeds. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Google prioritising geotagged posts in search results, for example. That would probably make Google’s search on mobile devices much more compelling, anyhow.

Many publishers and app developers, large and small, have complained that the social platforms are breaking their promises and closing down access, becoming enemies of the open internet and being difficult to work with. The federated messaging network is being killed off, they say. Maybe it’s just now being born.

Media organisations need to look again at RSS, open APIs, geotagging, open licensing, and better ways of collaborating. You may have abandoned it in the past, but RSS would have you back in a heartbeat. And if RSS is insufficient then any location-aware API standard could be the meeting place where we rebuild the open internet together.

It won’t solve all your problems, but it could certainly solve a few, including new revenue streams. And it’s conceivable that critical mass around open location-based feeds would mean that the internet becomes a stronger force for us all, protected from nascent platforms whose their future selves may not share the same vision that got them off the ground in the first place.

To get more articles like this sent direct to your inbox, sign up for free membership to the Guardian Media Network. This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.

They had a fully catered event including an open bar with some good whiskey. The schwag bag included the Flip digital video camera (wow!). There were a small handful of very basic demos on the floor from the usual suspects (Slide, iLike, Flixster, etc.). And the presentation was short and sweet so we could get back to socializing.

They had a fully catered event including an open bar with some good whiskey. The schwag bag included the Flip digital video camera (wow!). There were a small handful of very basic demos on the floor from the usual suspects (Slide, iLike, Flixster, etc.). And the presentation was short and sweet so we could get back to socializing.

There must be kitchen design experts around the world I can learn from. Equally, I’m sure there is a guy around the corner from me who can give me some tips on local services. Will Architectural Digest or Home & Garden connect me to these different people? No. Will The San Francisco Chronicle connect us? No.

There must be kitchen design experts around the world I can learn from. Equally, I’m sure there is a guy around the corner from me who can give me some tips on local services. Will Architectural Digest or Home & Garden connect me to these different people? No. Will The San Francisco Chronicle connect us? No.